Bernard Baran

What kind of a man would possess the indifference to send an innocent human being to jail for 22 years to further his own career? Since James LaMountain’s press release about his encounter with “Judge” Daniel Ford in Superior Court, I did a lot of reading about the atrocity perpetrated against Bernard Baran in which “Judge” Daniel A. Ford was instrumental as a prosecutor at that time. I wish that a lot of people would take the time and read about the Baran case and show their support for Bernard

Baran. It is also important that as many individuals as possible manifest their outrage about the fact that this sinister individual Daniel Ford is still a judge, a judge that was appointed by Michael Dukakis back in April of 1989. Thank you Mr. Dukakis!

Baran. It is also important that as many individuals as possible manifest their outrage about the fact that this sinister individual Daniel Ford is still a judge, a judge that was appointed by Michael Dukakis back in April of 1989. Thank you Mr. Dukakis!

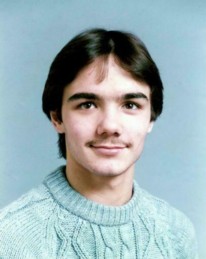

On the left, picture of Bernard Baran before he met prosecutor Daniel Ford; on the right after he spent 22 years as an innocent man in jail.

Peter Frei

Edit - Delete

Comments:

Posted on 27 Oct 2009, 9:39 by Danny in the DarkWant More Iinfo

I wish you'd tell us more about this case..ie...what's the crime he ALLEGEDLY committed - when - where - what evidence convicted him - is he still in jail/where?....etc. etc. You ask us to show our support - how - what should readers do if we agree with you.

_________________________________________________________________

Posted on 27 Oct 2009, 10:21 by Peter Frei

More Info

To "Danny in the Dark," if you google the term ("Bernard Baran" judge ford) you will get 1100 results with more information than you have time to read, many of which are blogs like this one where you can leave a comment. If there is enough interest I will personnaly file a complaint with the Board of Bar Overseers of the Supreme Judicial Court.

Here is just one piece written about Bernard Baran by Radley Balko on August 17, 2009:

This June, District Attorney David Capeless of Berkshire County, Massachusetts announced that he was dropping all charges against 44-year-old Bernard Baran, a man who has spent half his life behind bars on child molestation charges that the state no longer has the confidence to retry.

Baran was convicted in January 1985 of molesting six children at a pre-Kindergarten daycare facility in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. He was released on bond in 2006 after an appeals court determined [PDF] that his trial attorney had been incompetent and that the prosecution may have withheld key exculpatory evidence. Baran says that during his jail term he was raped and beaten more than 30 times, necessitating six different transfers to new correctional institutions. Such is the cost the prison system exacts on an openly gay man convicted of molesting children.

Baran was one of the first people in the country to be prosecuted in the daycare sex abuse panic of the 1980s, a bizarre, nationwide hysteria fed by fears of satanism, homophobia, and a wing of child psychology that used unproven interrogation techniques critics say caused children to recount sexual incidents thatnever took place.

While Baran's case has been covered extensively in Massachusetts, and recently in the national media, one aspect of it still hasn't really been examined. Prosecutor Daniel Ford likely engaged in serious misconduct and open bigotry in winning his conviction of Baran. Yet in 25 years, Ford has never been investigated or disciplined for his role in the case. And since 1989, Ford has sat as a judge on the Massachusetts Superior Court. Ford's career trajectory and lack of accountability is the far too familiar product of the backward incentive structure that prosecutors work under. Convictions produce rewards, while abuse rarely comes with a penalty.

The most serious allegation against Ford in this case concerns an edited video interview with the children he presented to the grand jury that indicted Baran. According to court documents, the video shows several children alleging that Baran had sexually abused them. But edited out was footage in which some of the children denied any abuse by Baran, accused other members of the daycare faculty of abuse or of witnessing abuse, and, most importantly, depicted interrogators asking the same questions over and over—even after repeated denials—until a child gave them an affirmative answer. Some children were even given rewards for their answers.

Withholding the unedited video from the grand jury was itself an act of misconduct. And Ford may also have withheld it from Baran's trial attorney. We can only say "may" because there's never been a hearing, and Baran's trial attorney was far from competent. (Judge Ford did not respond to multiple requests for comment.) In granting Baran a new trial in 2006 [PDF], Massachusetts Superior Court Judge Francis Fecteau never moved beyond the inadequacy of Baran's lawyer. Harvey Silverglate, one of Baran's appellate attorneys (and also a Reason contributor), says Fecteau's passing over the misconduct claims was entirely appropriate. "For the purposes of judicial economy, judges only focus on what's necessary to make a ruling," he says. "Judge Fecteau is a hero, here. I don't fault him at all."

When the case reached the state appeals court, the justices there not only upheld Fecteau's ruling [PDF], they looked more closely at Ford's possible misconduct. "While the record does not settle the question whether the unedited videotapes were deliberately withheld by the prosecution," the ruling read, "there are indications in the trial transcript consistent with that contention."

The appellate court further noted that it took years for Baran's appellate lawyers to get prosecutors to turn over the unedited tapes. Baran's attorneys originally filed a motion for the tapes in 2000. For three years, then District Attorney Gerard Downing, who assisted in Baran's original trial, claimed to be unable to locate the tapes. When Downing died of a sudden heart attack in December 2003, David Capeless took over as D.A. When a court ordered Capeless to find the tapes, he was able to produce them within months. The appellate court opinion cited other examples of Ford failing to turn over exculpatory evidence, too, including evidence that two of the children who accused Baran may have suffered prior sexual abuse.

The case against Baran was also awash in homophobia. According to court documents, the first parents to come forward with accusations against Baran in September 1984 had just days earlier registered a complaint with the center upon noticing Baran was "queer" by the way he walked and talked. The boy's mother, who thought gays "shouldn't be allowed out in public" much less permitted to work at daycare centers, said that she "didn't want no homo" watching her son.

When that child later tested positive for gonorrhea of the throat, Ford used the test against Baran at trial, even though A) the child never accused Baran of forcing him to perform oral sex, B) the child, in fact, specifically denied having sexual contact with Baran on the witness stand, C) Baran tested negative for gonorrhea, D) the boy had told his mother two months prior that his stepfather had orally raped him, and E) on the very day Baran was convicted, charges against the stepfather were turned over to the D.A.'s office for possible prosecution. Baran's counsel was never informed of the allegation against the stepfather. Addressing the gonorrhea issue in his closing arguments, Ford implied that Baran's "lifestyle" made it probable that he contracted gonorrhea at other times and knew how to quickly eradicate it to cover his tracks.

Baran has said he isn't sure he wants to endure a lawsuit, but even if he did such a suit would still be unlikely to get to Ford. Prosecutors enjoy absolute immunityfrom civil rights lawsuits, even in cases of misconduct that lead to false convictions. And they're rarely disciplined in other ways, either. Appeals courts rarely even mention prosecutors by name when criticizing their conduct. (Ford wasn't named in the Massachusetts appellate court's decision.) Courts and bar associations also rarely hand down professional sanctions. According to a study released earlier this year by the advocacy group The Justice Project, "Despite the prevalence of prosecutorial misconduct all over the country, states have consistently failed to investigate or sanction prosecutors who commit acts of misconduct in order to secure convictions."

The only way Ford's actions in the Baran case could now be examined would be for one of the state's legal ethics boards to open an investigation, either on its own or in response to a complaint. Silverglate says that if there's no action in the coming months, he may file a complaint himself.

Radley Balko is a senior editor at Reason magazine

_________________________________________________________________

Posted on 27 Oct 2009, 10:32 by Bloggie

Read the comments in the press release

I read the comments in LaMountains press release on this blog including the actual transcripts from the children that make it clear as to the details in this matter.

_________________________________________________________________

Posted on 28 Oct 2009, 15:11 by Prison Camp America

More info ? No outrage?

The Elephant Under the Rug

Dear Friend of Justice,

Jim D’Entremont and I first became aware of the Baran case in 1995, but all we knew about it was the information found on Jonathan Harris’s web site. Our involvement really began in June of 1998, at the urging of our friend, Debbie Nathan.

It took us another year to get essential documents in the case. When we read them, we were appalled. We were especially appalled at the conduct of the prosecutor, Daniel A. Ford.

Ford was ambitious and ruthless. He used the Baran case to make his career. This strategy was successful. Governor Michael Dukakis made him a Superior Court Judge twenty years ago. He remains a judge today. He is an important member of the power structure of Berkshire County.

Thus far, criticism of Ford has been very muted. He is almost never mentioned by name in press accounts of the Baran case. Judge Fecteau made no ruling on the charges of prosecutorial misconduct when he granted Baran a new trial. I do not fault Fecteau for this. I believe he was doing what he thought would be most effective in achieving the ends of justice. Criticizing a brother judge could have eventually caused the waters to be muddied and thus blunted the effectiveness of his excellent decision.

But the Massachusetts Appeals Court has decided that the time has finally come to start talking about the elephant that’s been hiding under the rug.

The Court needed to say nothing about prosecutorial misconduct, because no ruling had been made on that issue. Never the less, they found they had quite a bit to say.

Several things troubled them:

Dan Ford deliberately withheld from the defense the videotapes of the child interviews — interviews which contained a huge mass of exculpatory material.

Dan Ford deliberately withheld from the defense police reports and DSS materials indicating that at least two of the children were very likely sexually abused by someone other than Baran. [Not surprisingly, no charges were ever brought against these men, who were very likely real child abusers.]

Dan Ford deliberately misled the Grand Jury by showing them a composite videotape with all exculpatory material excised.

Dan Ford turned over material from his case files to the law firm representing the mother of one of the alleged victims.

I think that bill of indictment should be sufficient to have Dan Ford impeached and disbarred, if not sent to prison for obstruction of justice.

A fifth charge is intimidation of potential defense witnesses. I think this affidavit gives us a good glimpse of Judge Ford’s moral character. (I believe there were other potential witnesses silenced by threats from Dan Ford as well.)

I suppose there are some who would excuse Dan’s Ford misbehavior by saying that he truly believed in Baran’s guilt and was sincerely interested in protecting children. But don’t believe that.

I believe that the Appeals Court has fired a warning shot across Dan Ford’s bow.

It will be interesting to see how he — and his chief protector, DA David Capeless –will respond.

But however they respond, the Baran case is now over. Capeless might appeal and the SJC might decide to hear it. But I can see no way the SJC could — or would — invalidate the two excellent decisions written by Judge Fecteau and by the Massachusetts Appeals Court. And there is no way this case could ever be retried.

Bernard Baran is not a criminal. In my opinion, Dan Ford is.

But the elephant’s days of hiding under the rug are coming to an end.

-Bob Chatelle

_________________________________________________________________

Posted on 4 Nov 2009, 7:46 by Paul Schindler

Finally a free man

Twenty-four years after his conviction on charges that he raped and abused pre-schoolers in his care, Bernard Baran is finally a free man. Last month, as Arthur S. Leonard reported in Gay City News, the Appeals Court of Massachusetts finally affirmed a 2006 lower court ruling that the gay man, 19 at the time, did not receive a fair trial in 1985.

Even after the Appeals Court ruled, Baran was still in legal jeopardy, given the fact that the Berkshire County prosecutor still had the option to retry the case. On June 9, District Attorney David F. Capeless filed paperwork with the court indicating that, "in the best interests of justice," he would not pursue the case further.

Justice Barbara Lenk's opinion for the appellate panel points up an unfortunate miscarriage of justice Baran suffered. One family, unhappy that a gay man was involved in their child's care, seems to have fabricated charges against him and then enlisted other families in their crusade. Suggestive questioning of the pre-schoolers, ages three and four, documented on interview tapes carefully edited to omit exculpatory material, were presented to both the grand jury and the trial jury. The unedited versions were never provided to Baran's counsel.

The appeals panel also found the trial was tainted by improper testimony as well as improper argument by prosecutor Daniel Ford -- now a judge, probably complicating Baran's efforts at vindication. The result was an hysterical stampede to convict Baran on several counts of child rape and sexual abuse and punish him with multiple life sentences. He spent more than 20 years in prison, enduring mistreatment by his fellow inmates, before the 2006 ruling finally led to his release in 2006.

Still, in the three years since then, Baran faced the continual risk of re-incarceration in addition to onerous monitoring by law enforcement officials.

_________________________________________________________________